Human Origins: Rethinking Our Fossil Ancestors

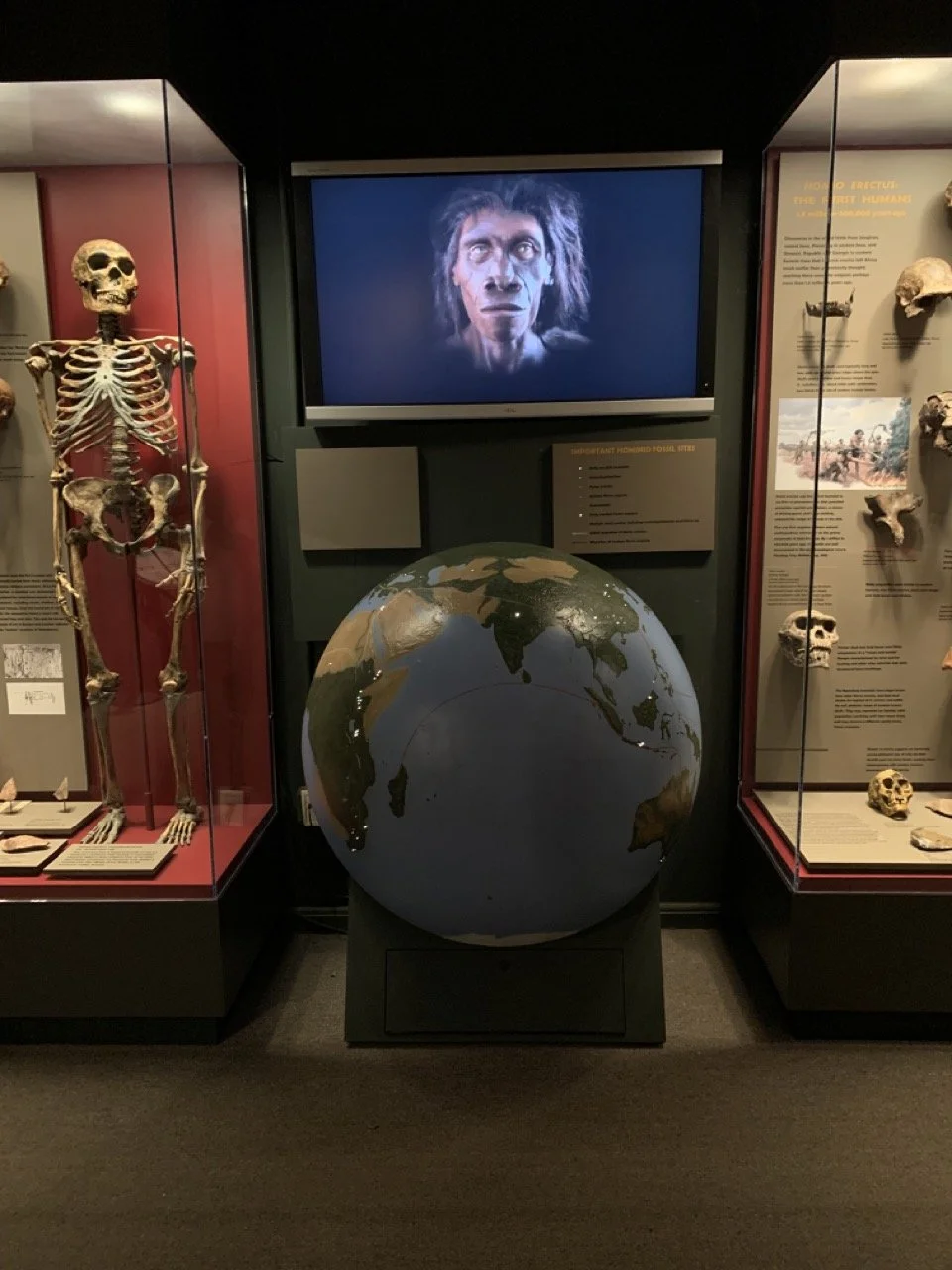

The McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture is housed in Circle Park at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. The museum boasts extensive geological and paleontological collections, as well as the only human evolution exhibit in the state: Human Origins: Rethinking Our Fossil Ancestors.

The exhibit opened to the public in 2012, and over the years had two minor additions to incorporate new fossil findings, one in 2014, another in 2018. In 2021, I was tasked with evaluating the exhibit’s content and impact, identifying outdated, inaccurate, or problematic exhibit content, and submitting a proposal for updating the exhibit. This project included consultation with experts, visitor observation and evaluation, and interviews with staff and local educators. The final proposal updated exhibit goals and main messages to better reflect the McClung’s commitment to acting as a service-based community museum, made recommendations for improvements in accessibility and interactivity, and made extensive updates to label copy. The exhibit’s content included discussion of basic taxonomy, human anatomy, evolutionary concepts, fossil and archaeological remains of hominin ancestors, and reflective questions inviting visitors to consider the history of evolution education in Tennessee.

-

Label 1.1: The Tree of Life

Animals can be categorized based on both their unique characteristics and evolutionary relationships between groups.

These categories, or ‘taxa’, are generally broken down into levels, from more generalized to more specific:

Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and species.

Your unique formula is

Kingdom ‘Animalia’

Phylum ‘Chordata’

Class ‘Mammalia’

Order ‘Primates’

Family ‘Hominidae’

Genus ‘Homo’

and species ‘sapiens’.

As a human, you are a mammal. You are also a primate, which is one of the most diverse orders in the animal kingdom. This means you have many primate relatives that look very different from you! You are also a member of the family Hominidae, which makes you a ‘Great Ape’. Other great apes include gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans.

—

Label 9.2: Later Genus Homo

Kabwe I

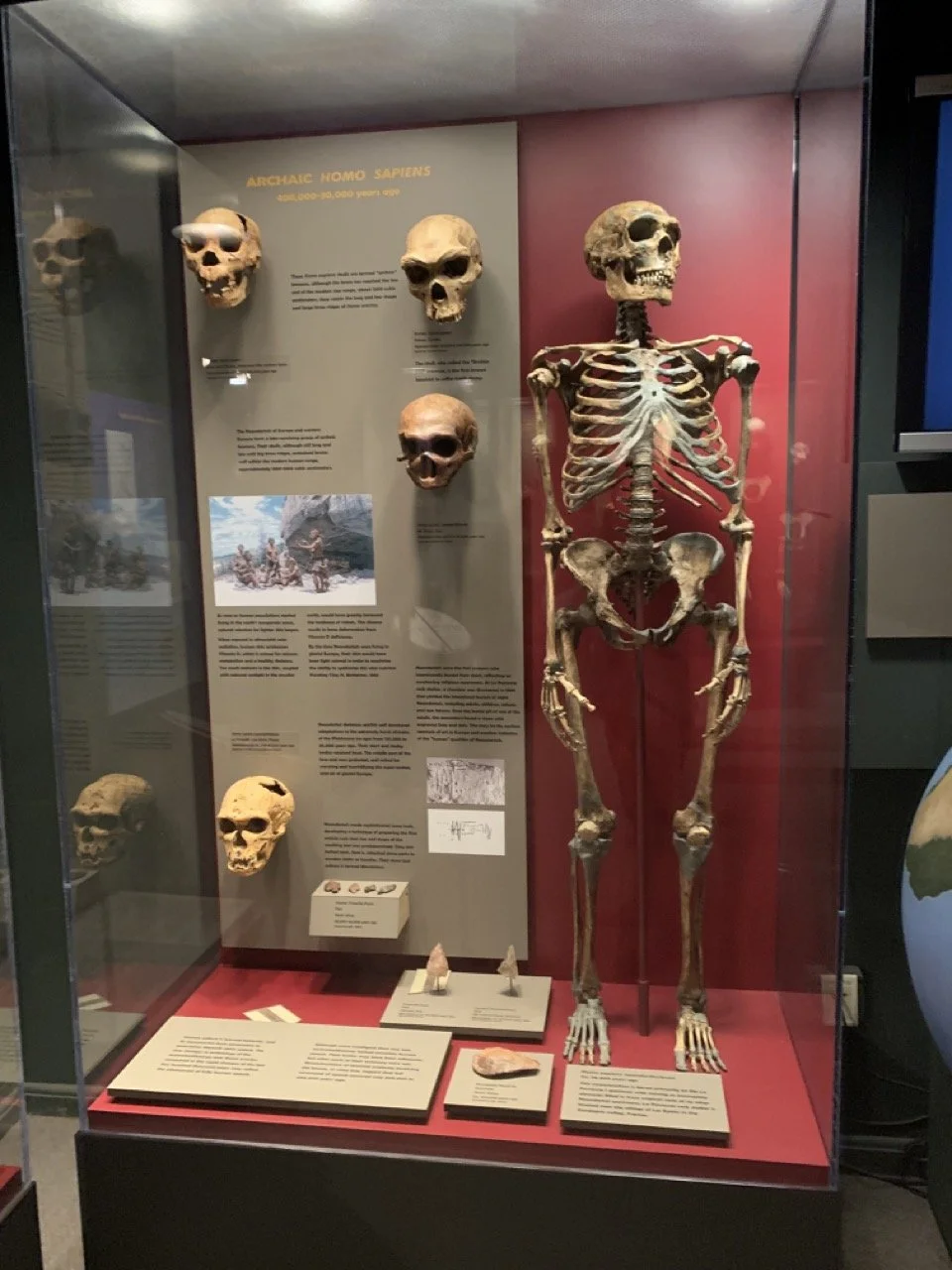

This skull, also called the “Broken Hill cranium,” is the earliest example of a human ancestor suffering from tooth decay.

His rotted teeth are important, not because of what they say about the individual, but because of what his teeth may mean about the other early humans living alongside him. Severe tooth decay can indicate advanced age, and living with rotten teeth could evidence complex behaviors like care-taking. Archaeological evidence suggests that these human ancestors survived on a diet of tough nuts and vegetation. Aged, toothless individuals like the Broken Hill cranium may have needed additional food processing—like pre-chewing— to survive.

Our Ice Age Cousins

The Neanderthals of Europe and western Eurasia were a late-surviving species of the genus Homo. Their skulls still featured prominent brow ridges, but contained brains well-within the modern human size range, approximately 1300-1500 cubic centimeters.

Neanderthal skeletons were well-adapted to the harsh Pleistocene ice ages. Neanderthals’ short limbs and stocky bodies retained body heat around vital organs. The mid-face and nose projected, making their airways well-suited for warming and humidifying the super-cooled, arid air of glacial Europe.

Neanderthals were capable of many of the same behaviors as modern humans. Fossil evidence from tooth enamel indicates that Neanderthals likely used medicinal plants. Archaeological findings show that they wore clothing and jewelry, and perhaps even practiced burial rituals. The anatomy of their throat and skull indicates that they were even capable of complex speech.

Neanderthals made sophisticated stone tools, developing a technique of “preparing” flint, such that the size and shape of the resulting blade was determined at the first strike. Neanderthals also “hafted” tools, attaching stone blades to wooden shafts or handles to create spears. Their toolmaking culture is called Mousterian.

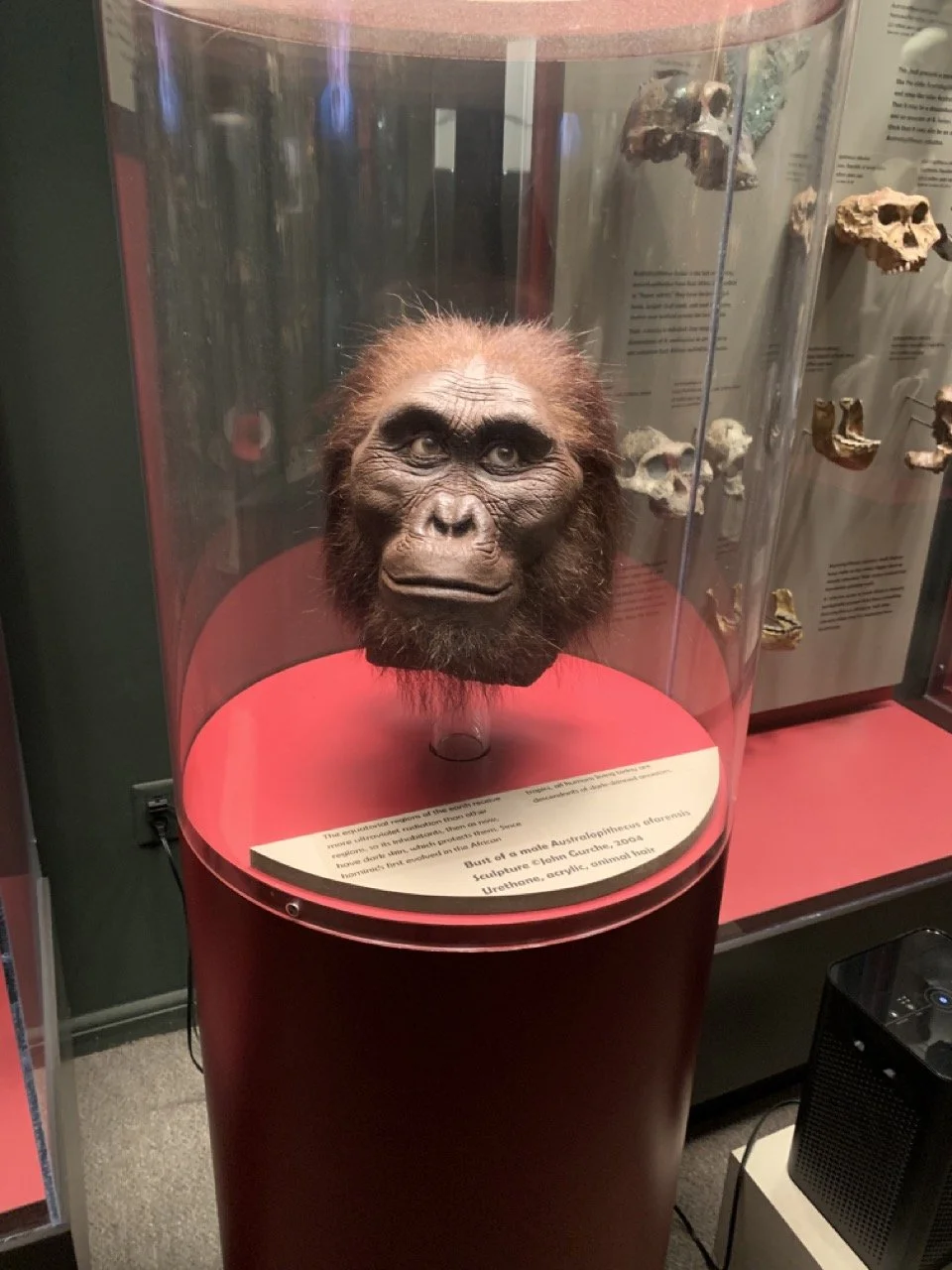

Call out text: Human culture is learned behavior, and its transmission from generation to generation depends on communication. The slow technological changes of the australopithecines and Homo erectus, compared to the rapid changes in tools seen in Homo neanderthalensis and early Homo sapiens, may reflect that complex speech was finally attained. Although they were more intelligent than modern non-human apes, australopithecines like “Lucy” lacked human speech. Their brains may have been adequate, but other parts of their anatomy were not. Reconstructions of hominid anatomy involving the larynx, or voice box, suggest that the capacity to vocalize like modern humans occurred only 300,000 to 400,000 years ago.